Memento Mori

The most important thing in life is Death.

Yet he seems to come from some other domain, another dimension. He is the strangest visitor in this “world of the living.” Although he seems to be a part of life, his mere appearance extinguishes it. He is both a part of and extraneous to life. He is both an event in life and a non-event. While we are alive, he is absent; once he arrives, we are gone. We can never truly experience death. However, while we are alive, he makes his appearance every single day: he takes with him so many of those around us. So we come to know of him. Just as we know of the lives of celebrities or royalty: from a distance.

He is both “a person” with whom we can attempt to relate in our meditative moments of solitude, and a cold impersonal natural force – mysterious, unfathomable, distant. But although his elusive nature and substance will remain forever shrouded in these paradoxes, and although we can never know him in person, we still know that he is the most important thing in our life. For his mere existence tells us that our life has an expiration date. Though we may not know when that date is, we know for certain that it exists.

Thinking about and discussing death has become socially uncomfortable in modern times. Death and our preoccupation with it has been relegated to specialist conferences, to expert physicians and psychologists. But it was not always like that. In Ancient Egypt, death was so central to everyday life that there are many treatises and books written about the “Egyptian obsession with death.” The Ancient Romans, who were permanently at war and often experienced the death of their youth, developed a system of ideas and meditations related to death. The most important of them was the idea of remembering death – memento mori. “Remember death” (or literally, “remember dying,” since mori is the infinitive of the verb “to die”) was the incitement to meditate on death and one’s mortality regularly, if not every single day. One of the functions of memento mori was to moderate pride. So it was customary for a Roman general, upon his victorious return from battle, amid the compliments and honors from the cheering crowds during his triumphant parade, in order to avoid falling victim to delusions of grandeur, to have had a slave stationed behind him, repeating in his ear: “memento mori.”

A fragment from Danse Macabre (1633) by Bernt Notke in St Nicolas Church, Tallinn, Estonia. Death is about to “dance” with the royal couple.

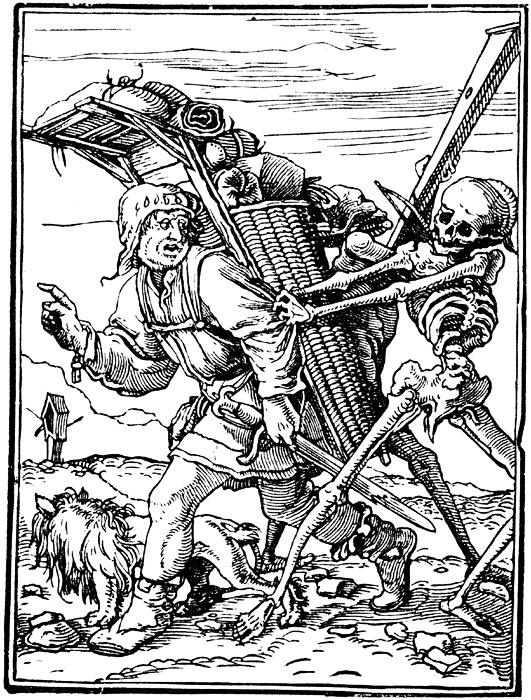

Later on, in Christianity, memento mori became associated with Holy Fear and with being mindful of one’s deeds. Our life on earth was significant only so far as it could be related to the spiritual work necessary to earn Eternal Life. The famous danse macabre paintings from late medieval times onward would show a round dance headed by Death, or a chain of alternating dead and live dancers. From the highest ranks of the medieval hierarchy (usually pope and emperor) down to its lowest (beggar, peasant, and child), each mortal’s hand is taken by death, portrayed as a skeleton or a decayed body. Hans Holbein’s woodcut drawings from the early sixteenth century, which show Death intruding violently amid the living in the most inopportune moments of everyday life, are some of the strongest portrayals of the idea that death is both a part of life and also extraneous to it.

One of my favorite of Holbein’s woodcut series: Death pulls back the peddler, who is on his way to the market. Ironically, the peddler apparently points to where he is going, and tells Death that he still has work to do!

One of my favorite of Holbein’s woodcut series: Death pulls back the peddler, who is on his way to the market. Ironically, the peddler apparently points to where he is going, and tells Death that he still has work to do!

In Buddhism, meditating on one’s mortality is usually related to procrastination: The amount of time you have for spiritual practice is small, so working hard right now is imperative. Consider this very potent excerpt from the late teacher Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche:

Now is the time to prepare for death. In general, we are always very worried about the future. We make strenuous efforts to ensure that in the future we will not run out of money, run out of food or be without clothes. But of all future events, isn’t death the most crucial? Out of fear of assassins, kings and presidents surround themselves with guards; but what about the most lethal assassin of all, who can move in at any moment with no one to stop him?…We may have many friends and acquaintances at the moment, perhaps many enemies too, but as soon as death falls upon us we shall leave all of them behind, like a hair pulled out of a slab of butter.

Many modern Westerners are, well, mortified when they are told to meditate on death! “What are the benefits of memento mori?” they ask. The benefits are too many to enumerate, and they become palpable only after one begins practicing. But we could mention a few of the most central:

1) Stop Squandering Time: Do not forget in the midst of play and fun that there is serious work to be done within your life’s time.

2) Stop Procrastinating: A little bit different from squandering time, procrastination always assumes that tomorrow is as good a time to do something as today. Yet today is a given; tomorrow is uncertain.

3) Sifting trivialities from what is important: In the grand scheme of things, where death can strike at any moment, what is the true value of the triviality with which I am now preoccupied?

4) Moderating Pride: Imagine the Roman slave’s whispered words in your ears!

5) Relinquishing Control: We feel we control everything in our life, but in reality we do not control the most important things – the era we were born into, our parents and nationality, the fact that we age, our health, or whether our heart will still be beating a few minutes later.

6) Experiencing Gratefulness: I am grateful I am still alive today. And healthy, and sane, and enjoying all the gifts of life here and now.

7) Living for Eternity (but not in the medieval Christian sense referred to above): If this is the last day of my life, how can I make it “meaningful with respect to the eternity that will follow it”? Death puts an end to my life, but not to my life’s creations. What then ought those to be?

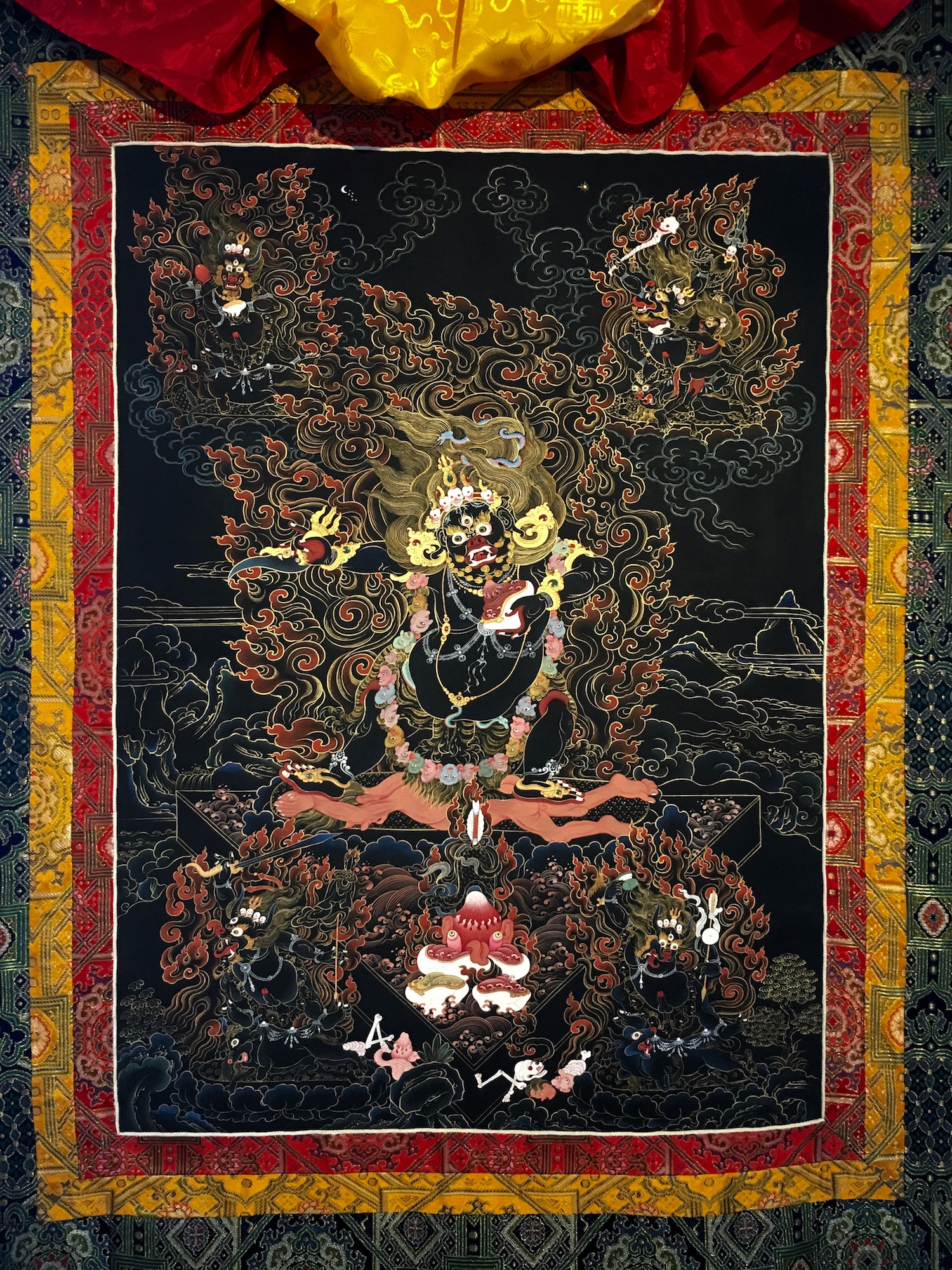

Every day I sit opposite a beautiful Tibetan thangka called “The Five Yamas (Deaths)” and practice memento mori. The main figure of the painting, the central Yama, has a necklace of human heads, consumes body parts, and stands on a crushed man who surrenders to his unavoidable fate. I will soon be that crushed man. Maybe in five years from now, or five months or five weeks.

“The Five Yamas”, by the Tibetan artist Tashi Dhargyal.